I Fixed-Size Data

1 Arithmetic

When a programmer studies a new language, the first item of business is the language’s “arithmetic,” meaning its basic forms of data and the operations that a program can perform on this data. At the same time, we need to learn how to express data and how to express operations on data.

write "(",

write down the name of a primitive operation op,

write down the arguments, separated by some space, and

write down ")".

(+ 1 2)

It is not necessary to read and understand the entire chapter in order to make progress. As soon as you sense that this chapter is slowing you down, move on to the next one. Keep in mind, though, that you may wish to return here and find out more about the basic forms of data in BSL when the going gets rough.

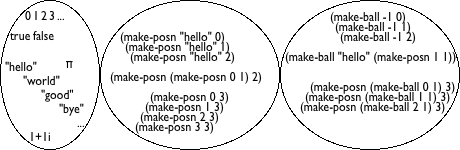

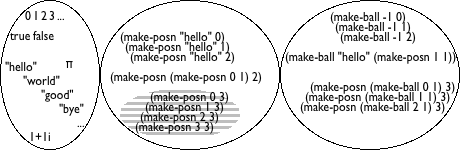

The rest of this chapter introduces four forms of data: numbers, strings, images, and Boolean values. It also illustrates how these forms of data are manipulated with primitive operations, often called built-in operations or primitives. Because of the nature of BSL, this book also refers to primitives as functions though you will need to read the remaining chapters of this first part to understand the reason for this terminology.

1.1 The Arithmetic Of Numbers

Most people think “numbers” and “operations on numbers” when they hear “arithmetic.” “Operations on numbers” means adding two numbers to yield a third; subtracting one number from another; or even determining the greatest common divisor of two numbers. If we don’t take arithmetic too literally, we may even include the sine of an angle, rounding a real number to the closest integer, and so on.

The BSL language supports Numbers and arithmetic in all these forms. As discussed in the Prologue, an arithmetic operation such as + is used like this:

(+ 3 4)

that is, in prefix notation form. Here are some of the operations on numbers that our language provides: +, -, *, /, abs, add1, ceiling, denominator, exact->inexact, expt, floor, gcd, log, max, numerator, quotient, random, remainder, sqr, and tan. We picked our way through the alphabet, just to show the variety of operations. Explore what these do in the interactions area, and then find out how many more there are and what they do.

If you need an operation on numbers that you know from grade school or high school, chances are that BSL knows about it, too. Guess its name and experiment in the interaction area. Say you need to compute the sin of some angle; try

> (sin 0) 0

and use it happily ever after. Or look in the HelpDesk. You will find there that in addition to operations, BSL also recognizes the names of some widely used numbers, for example, pi and e.You might not know e if you have not studied calculus. It’s a real number, close to 2.718, commonly called “Euler’s constant.”

When it comes to numbers, BSL programs may use natural numbers, integers, rational numbers, real numbers, and complex numbers. We assume that you have heard of the first four. The last one may have been mentioned in your high school. If not, don’t worry; while complex numbers are useful for all kinds of calculations, a novice doesn’t have to know about them.

A truly important distinction concerns the precision of numbers. For now, it is important to understand that BSL distinguishes exact numbers and inexact numbers. When it calculates with exact numbers, BSL preserves this precision whenever possible. For example, (/ 4 6) produces the precise fraction 2/3, which DrRacket can render as a proper fraction, an improper fraction, or as a mixed decimal. Play with your computer’s mouse to find the menu that changes the fraction into decimal expansion and other presentations.

Some of BSL’s numeric operations cannot produce an exact result. For example, using the sqrt operation on 2 produces an irrational number that cannot be described with a finite number of digits. Because computers are of finite size and BSL must somehow fit such numbers into the computer, it chooses an approximation: #i1.4142135623730951. As mentioned in the Prologue, the #i prefix warns novice programmers of this lack of precision. While most programming languages choose to reduce precision in this manner, few advertise it and fewer even warn programmers.

Note The word Number refers to a wide variety of numbers, including counting numbers, integers, rational numbers, real numbers, and even complex numbers. If we wish to be precise, we use appropriate words: Integer, Rational, Real, and so on. We may even refine these notions using such standard terms as PositiveInteger, NonnegativeNumber, etc.

Exercise 1. The direct goal of this exercise is to create an expression that computes the distance of some specific Cartesian point (x,y) from the origin (0,0). The indirect goal is to introduce some basic programming habits, especially the use of the interactions area to develop expressions.

The values for x and y are given as definitions in the definitions area (top half) of DrRacket:The expected result for these values is 5 but your expression should produce the correct result even after you change these definitions.Just in case you have not taken geometry courses or in case you forgot the formula that you encountered there, the point (x,y) has the distance

from the origin. After all, we are teaching you how to design programs not how to be a geometer.To develop the desired expression, it is best to hit RUN and to experiment in the interactions area. The RUN action tells DrRacket what the current values of x and y are so that you can experiment with expressions that involve x and y:Once you have the expression that produces the correct result, copy it from the interactions area to the definitions area, right below the two variable definitions.To confirm that the expression works properly, change the two definitions so that x represents 12 and y stands for 5. If you click RUN now, the result should be 13.

Your mathematics teacher would say that you computed the distance formula. To use the formula on alternative inputs, you need to open DrRacket, edit the definitions of x and y so they represent the desired coordinates, and click RUN. But this way of reusing the distance formula is cumbersome and naive. Instead, we will soon show you a way to define functions, which makes re-using formulas straightforward. For now, we use this kind of exercise to call attention to the idea of functions and to prepare you for programming with them.

1.2 The Arithmetic Of Strings

A wide-spread prejudice about computers concerns its innards. Many believe

that it is all about bits and bytes—

Programming languages are about calculating with information, and information comes in all shapes and forms. For example, a program may deal with colors, names, business letters, or conversations between people. Even though we could encode this kind of information as numbers, it would be a horrible idea. Just imagine remembering large tables of codes, such as 0 means “red” and 1 means “hello,” etc.

Instead most programming languages provide at least one kind of data that deals with such symbolic information. For now, we use BSL’s strings. Generally speaking, a String is a sequence of the characters that you can enter on the keyboard enclosed in double quotes, plus a few others, about which we aren’t concerned just yet. In Prologue: How to Program, we have seen a number of BSL strings: "hello", "world", "blue", "red", etc. The first two are words that may show up in a conversation or in a letter; the others are names of colors that we may wish to use.

> (string-append "what a " "lovely " "day" " for learning BSL") "what a lovely day for learning BSL"

Then use string primitives to create an expression that concatenates prefix and suffix and adds "_" between them. When you run this program, you will see "hello_world" in the interactions area.See exercise 1 for how to create expressions using DrRacket.

1.3 Mixing It Up

string-length consumes a string and produces a (natural) number;

string-ith consumes a string s together with a natural number i and then extracts the one-character substring located at the ith position (counting from 0); and

number->string consumes a number and produces a string.

> (string-length 42) string-length: expects a string, given 42

(+ (string-length "hello world") 60)

(+ (string-length "hello world") 60) = (+ 11 60) = 71

(+ (string-length (number->string 42)) 2) = (+ (string-length "42") 2) = (+ 2 2) = 4

(+ (string-length 42) 1)

Then create an expression using string primitives that adds "_" at position i. In general this means the resulting string is longer than the original one; here the expected result is "hello_world".Position means i characters from the left of the string—but computer scientists start counting at 0. Thus, the 5th letter in this example is "w", because the 0th letter is "h". Hint: when you encounter such “counting problems” you may wish to add a string of digits below str to help with counting: See exercise 1 for how to create expressions in DrRacket.

Exercise 4. Use the same setup as in exercise 3. Then create an expression that deletes the ith position from str. Clearly this expression creates a shorter string than the given one; contemplate which values you may choose for i.

1.4 The Arithmetic Of Images

Images represent symbolic data somewhat like strings. To work with images, use the "2htdp/image" teachpack. Like strings, you used DrRacket to insert images wherever you would insert an expression into your program, because images are values just like numbers and strings.

circle produces a circle image from a radius, a mode string, and a color string;

ellipse produces an ellipse from two radii, a mode string, and a color string;

line produces a line from two points and a color string;

rectangle produces a rectangle from a width, a height, a mode string, and a color string;

text produces a text image from a string, a font size, and a color string; and

triangle produces an upward-pointing equilateral triangle from a size, a mode string, and a color string.

> (star 12 "solid" "green")

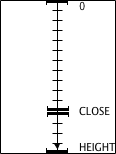

image-width determines the width of a given image in terms of pixels;

image-height determines the height of an image;

A proper understanding of the third kind of image primitives—

overlay places all the images to which it is applied on top of each other, using the center as anchor point. You encountered this function in the Arithmetic And Arithmetic.

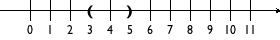

overlay/xy is like overlay but accepts two numbers—

x and y— between two image arguments. It shifts the second image by x pixels to the right and y pixels down — all with respect to the image’s center; unsurprisingly, a negative x shifts the image to the left and a negative y up. overlay/align is like overlay but accepts two strings that shift the anchor point(s) to other parts of the rectangles. There are nine different positions overall; experiment with all possibilities!

empty-scene creates an framed rectangle of a specified width and height;

place-image places an image into a scene at a specified position. If the image doesn’t fit into the given scene, it is appropriately cropped.

add-line consumes an scene, four numbers, and a color to draw a line of that color into the given image. Again, experiment with it to find out how the four arguments work together.

(define cat

)

Create an expression that counts the number of pixels in the image. See exercise 1 for how to create expressions in DrRacket.

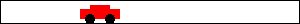

Exercise 6. Use the picture primitives to create the image of a simple automobile.

Exercise 7. Use the picture primitives to create the image of a simple boat.

Exercise 8. Use the picture primitives to create the image of a simple tree.

1.5 The Arithmetic Of Booleans

We need one last kind of primitive data before we can design programs: Boolean values. There are only two kinds of Boolean values: true and false. Programs use Boolean values for representing decisions or the status of switches.

- and not always picks the Boolean that isn’t given:

Finally, there is more to or and and than these explanations suggest, but to explain the extra bit requires another look at mixing up data in nested expressions.

Create an expression that computes whether b1 is false or b2 is true. So in this particular case, the answer is false. (Why?)See exercise 1 for how to create expressions in DrRacket. How many possible combinations of true and false can you think of for associating with b1 and b2?

1.6 Mixing It Up With Booleans

(define x 2)

(define x 0)

In addition to =, BSL provides a host of other comparison primitives. Explain what the following four comparison primitives determine about numbers: <, <=, >, >=.

Strings aren’t compared with = and its relatives. Instead, you must use string=? or string<=? or string>=? if you are ever in a position where you need to compare strings. While it is obvious that string=? checks whether the two given strings are equal, the other two primitives are open to interpretation. Look up their documentation, or experiment with them, guess, and then check in the documentation whether you guessed right.

The next few chapters introduce better expressions than if to express conditional computations and, most importantly, systematic ways for designing them.

(define cat

)

Create an expression that computes whether the image is "tall" or "wide". An image should be labeled "tall" if its height is larger or equal to its width; otherwise it is "wide". See exercise 1 for how to create expressions in DrRacket; as you experiment, replace the image of the cat with rectangles of your choice to ensure you know the expected answer.Now try the following modification. Create an expression that computes whether a picture is "tall", "wide", or "square".

1.7 Predicates: Know Thy Data

(* (+ (string-length 42) 1) pi)

(define in ...) (string-length in)

Every class of data that we introduced in this chapter comes with a predicate: string?, image?, and boolean?. Experiment with them to ensure you understand how they work.

In addition to predicates that distinguish different forms of data, programming languages also come with predicates that distinguish different kinds of numbers. In BSL, numbers are classified in two ways: by construction and by their exactness. Construction refers to the familiar sets of numbers: integer?, rational?, real?, and complex?. You may know these terms from secondary school.Evaluate (sqrt -1) in the interactions area and take a close look at the result. The result you see is the first so-called complex number anyone encounters. While your mathematics teacher may have told you that one doesn’t compute the square root of negative numbers, truth is that real mathematicians and programmers find it acceptable and useful to do so anyway. But don’t worry: understanding complex numbers is not essential to being a programmer. As for exactness, we have mentioned the idea before. For now, experiment with exact? and inexact? to make sure they perform the checks that their names suggest. Later we are going to discuss the nature of numbers in some detail.

(define in "hello")

Then create an expression that converts whatever in represents to a number. For a string, it determines how long the string is; for an image, it uses the area; for a number, it decrements the number, unless it is already 0 or negative; for true it uses 10 and for false 20.See exercise 1 for how to create expressions in DrRacket.

Exercise 12. Now relax, eat, sleep, and then tackle the next chapter.

2 Functions And Programs

As far as programming is concerned, arithmetic is half the game. The other half is “algebra.” Of course, our notion of “algebra” relates to the school notion of algebra just as much as the notion of “arithmetic” from the preceding chapter relates to the ordinary notion of grade-school arithmetic. The creation of real programs involves variables and thus functions, meaning basic notions from algebra. Once we can deal with functions, we can move on to programs, which “compose” functions to achieve their overall purpose.

2.1 Functions

From a high-level perspective, a program is a function. A program, like a function in mathematics, consumes inputs, and it produces outputs. In contrast to mathematical functions, programs work with a whole variety of data: numbers, strings, images, and so on. Furthermore, programs may not consume all of the data at once; instead a program may incrementally request more data or not, depending on what the computation needs. Last but not least, programs are triggered by external events. For example, a scheduling program in an operating system may launch a monthly payroll program on the last day of every month. Or, a spreadsheet program may react to certain events on the keyboard with filling some cells with numbers.

Definitions: While many programming languages obscure the relationship between programs and functions, BSL brings it to the fore. Every BSL programs consists of definitions, usually followed by an expression that involves those definitions. There are two kinds of definitions:

constant definitions, of the shape (define AVariable AnExpression), which we encountered in the preceding chapter; and

function definitions, which come in many flavors, one of which we used in the Prologue.

“(define (”,

the name of the function,

followed by one or more variables, separated by space and ending in “)”,

and an expression followed by “)”.

Before we explain why these examples are silly, we need to explain what

function definitions mean. Roughly speaking, a function definition

introduces a new operation on data; put differently, it adds an operation

to our vocabulary if we think of the primitive operations as the ones that

are always available. Like a primitive function, a defined function

consumes inputs. The number of variables determines how many inputs—

The examples are silly because the expressions inside the functions do not involve the variables. Since variables are about inputs, not mentioning them in the expressions means that the function’s output is independent of their input. We don’t need to write functions or programs if the output is always the same.

(define x 3)

For now, the only remaining question is how a function obtains its inputs. And to this end, we turn to the notion of applying a function.

write “(”,

write down the name of a defined function f,

write down as many arguments as f consumes, separated by some space, and

write down “)”.

> (f 1) 1

> (f 2) 1

> (f "hello world") 1

> (f true) 1

> (f) f: expects 1 argument, but found none

> (f 1 2 3 4 5) f: expects only 1 argument, but found 5

> (+) +: expects at least 2 arguments, but found none

Evaluating a function application proceeds in three steps. First, DrRacket determines the values of the argument expressions. Second, it checks that the number of arguments and the number of function parameters (inputs) are the same. If not, it signals an error. Finally, if the number of actual inputs is the number of expected inputs, DrRacket computes the value of the body of the function, with all parameters replaced by the corresponding argument values. The value of this computation is the value of the function application.

(string-append "hello" " " "world") = "hello world"

(define (opening first last) (string-append "Dear " first ","))

> (opening "Matthew" "Fisler") "Dear Matthew,"

(opening "Matthew" "Fisler") = (string-append "Dear " "Matthew" ",") = "Dear Matthew,"

To summarize, this section introduces the notation for function

applications—

Exercise 13. Define a function that consumes two numbers, x and y, and that computes the distance of point (x,y) to the origin.

In exercise 1 you developed the right-hand side for this function. All you really need to do is add a function header. Remember this idea in case you are ever stuck with a function. Use the recipe of exercise 1 to develop the expression in the interactions area, and then write down the function definition.

Exercise 14. Define the function cube-volume, which accepts the length of a side of a cube and computes its volume. If you have time, consider defining cube-surface, too.

Exercise 15. Define the function string-first, which extracts the first character from a non-empty string. Don’t worry about empty strings.

Exercise 16. Define the function string-last, which extracts the last character from a non-empty string. Don’t worry about empty strings.

Exercise 17. Define the function bool-imply. It consumes two Boolean values, call them b1 and b2. The answer of the function is true if b1 is false or b2 is true. Note: Logicians call this Boolean operation implication and often use the symbol =>, pronounced “implies,” for this purpose. While BSL could define a function with this name, we avoid that name because it is too similar to the comparison operations for numbers <= and >=, and it would thus easily be confused. See exercise 9.

Exercise 18. Define the function image-area, which counts the number of pixels in a given image. See exercise 5 for ideas.

Exercise 19. Define the function image-classify, which consumes an image and produces "tall" if the image is taller than it is wide, "wide" if it is wider than it is tall, or "square" if its width and height are the same. See exercise 10 for ideas.

Exercise 20. Define the function string-join, which consumes two strings and appends them with "_" in between. See exercise 2 for ideas.

Exercise 21. Define the function string-insert, which consumes a string and a number i and which inserts "_" at the ith position of the string. Assume i is a number between 0 and the length of the given string (inclusive). See exercise 3 for ideas. Also ponder the question how string-insert ought to cope with empty strings.

Exercise 22. Define the function string-delete, which consumes a string and a number i and which deletes the ith position from str. Assume i is a number between 0 (inclusive) and the length of the given string (exclusive). See exercise 4 for ideas. Can string-delete deal with empty strings?

2.2 Composing Functions

A program rarely consists of a single function definition and an

application of that function. Instead, a typical program consists of a

“main” function or a small collection of “main event handlers.” All of

these use other functions—

(define (letter fst lst signature-name) (string-append (opening fst) "\n\n" (body fst lst) "\n\n" (closing signature-name))) (define (opening fst) (string-append "Dear " fst ",")) (define (body fst lst) (string-append "We have discovered that all people with the last name " "\n" lst " have won our lottery. So, " fst ", " "\n" "hurry and pick up your prize.")) (define (closing signature-name) (string-append "Sincerely," "\n\n" signature-name))

> (letter "Matthew" "Fisler" "Felleisen") "Dear Matthew,\n\nWe have discovered that all people with ...\n\n"

In general, when a problem refers to distinct tasks of computation, a program should consist of one function per task and a main function that puts it all together. We formulate this idea as a simple slogan:

Define one function per task.

The advantage of following this slogan is that you get reasonably small functions, each of which is easy to comprehend, and whose composition is easy to understand. Later, we see that creating small functions that work correctly is much easier than creating one large function. Better yet, if you ever need to change a part of the program due to some change to the problem statement, it tends to be much easier to find the relevant program parts when it is organized as a collection of small functions.

Here is a small illustration of this point with a sample problem:

Sample Problem: Imagine the owner of a monopolistic movie theater. He has complete freedom in setting ticket prices. The more he charges, the fewer the people who can afford tickets. The less he charges, the more it costs to run a show because attendance goes up. In a recent experiment the owner determined a relationship between the price of a ticket and average attendance.

At a price of $5.00 per ticket, 120 people attend a performance. For each 10-cent change in the ticket price, the average attendance changes by 15 people. That is, if the owner charges $5.10, some 105 people attend on the average; if the prices goes down to $4.90, average attendance increases to 135. Let us translate this idea into a mathematical formula:avg. attendance = 120 - (change in price * (15 people / 0.10))

Stop! Explain the minus sign before you proceed.Unfortunately, the increased attendance also comes at an increased cost. Every performance comes at a fixed costs of $180 to the owner plus a variable cost of $0.04 per attendee.

The owner would like to know the exact relationship between profit and ticket price so that he can determine the price at which he can make the highest profit.

The problem statement specifies how the number of attendees depends on the ticket price. Computing this number is clearly a separate task and thus deserves its own function definition:

The function mentions the four constants—120, 5.0, 15, and 0.1— determined by the owner’s experience. The revenue is exclusively generated by the sale of tickets, meaning it is exactly the product of ticket price and number of attendees:

The number of attendees is calculated by the attendees function of course.The costs consist of two parts: a fixed part ($180) and a variable part that depends on the number of attendees. Given that the number of attendees is a function of the ticket price, a function for computing the cost of a show also consumes the price of a ticket and uses it to compute the number of tickets sold with attendees:

Again, this function also uses attendees to determine the number of attendees.Finally, profit is the difference between revenue and costs:

(define (profit ticket-price) (- (revenue ticket-price) (cost ticket-price))) Even the definition of profit suggests that we use the functions revenue and cost. Hence, the profit function must consume the price of a ticket and hand this number to the two functions it uses.

Exercise 23. Our solution to the sample problem contains several constants in the middle of functions. As One Program, Many Definitions already points out, it is best to give names to such constants so that future readers understand where these numbers come from. Collect all definitions in DrRacket’s definitions area and change them so that all magic numbers are refactored into constant definitions.

Exercise 24. Determine the potential profit for the following ticket prices: $1, $2, $3, $4, and $5. Which price should the owner of the movie theater choose to maximize his profits? Determine the best ticket price down to a dime.

(define (profit price) (- (* (+ 120 (* (/ 15 0.1) (- 5.0 price))) price) (+ 180 (* 0.04 (+ 120 (* (/ 15 0.1) (- 5.0 price)))))))

Exercise 25. After studying the costs of a show, the owner discovered several ways of lowering the cost. As a result of his improvements, he no longer has a fixed cost. He now simply pays $1.50 per attendee.

Modify both programs to reflect this change. When the programs are modified, test them again with ticket prices of $3, $4, and $5 and compare the results.

2.3 Global Constants

write “(define ”,

write down the name of the variable ...

followed by a space and an expression, and

write down “)”.

; the current price of a movie ticket (define CURRENT-PRICE 5) ; useful to compute the area of a disk: (define ALMOST-PI 3.14) ; a blank line: (define NL "\n") ; an empty scene: (define MT (empty-scene 100 100))

(define ALMOST-PI 3.14159) ; an empty scene: (define MT (empty-scene 200 800))

(define WIDTH 100) (define HEIGHT 200) (define MID-WIDTH (/ WIDTH 2)) (define MID-HEIGHT (/ HEIGHT 2))

Again, we use a simple slogan to remind you about the importance of constants:

Introduce definitions for all constants mentioned in a problem statement.

Exercise 26. Define constants for the price optimization program so that the price sensitivity of attendance (15 people for every 10 cents) becomes a computed constant.

2.4 Programs

a batch program consumes all of its inputs at once and computes its result. Its main function composes auxiliary functions, which may refer to additional auxiliary functions, and so on. When we launch a batch program, the operating system calls the main function on its inputs and waits for the program’s output.

an interactive program consumes some of its inputs, computes, produces some output, consumes more input, and so on. We call the appearance of an input an event, and we create interactive programs as event-driven programs. The main function of such an event-driven program uses an expression to describe which functions to call for which kinds of events. When we launch an interactive program, the main function informs the operating system of this description. As soon as input events happen, the operating system calls the matching functions. Similarly, the operating system knows from the description when and how to present the results of these function calls as output.

In this section we present simple examples of both batch and interactive programs.

Batch Programs As mentioned, a batch program consumes all of its inputs at once and computes the result from these inputs. Its main function may expect the arguments themselves or the names of files from which to retrieve the inputs; similarly, it may just return the output or it may place it in a file.

Once programs are created, we want to use them. In DrRacket, we launch batch programs in the interactions area so that we can watch the program at work.

Programs are even more useful if they can retrieve the input from some file and deliver the output to some other file. The name batch program originated from the early days of computing when a program read an entire file (or several files) and placed the result in some other file(s), without any intervention after the launch. Conceptually, we can think of the program as reading an entire file at once and producing the result file(s) all at once.

read-file, which reads the content of an entire file as a string, and

write-file, which creates a file from a given string.

> (write-file "sample.dat" "212") "sample.dat"

> (read-file "sample.dat") "212"

212 |

> (write-file 'stdout "212") 212

'stdout

Let us illustrate the creation of a batch program with a simple example. Suppose we wish to create a program that convertsThis book is not about memorizing facts, but we do expect you to know where to find them. Do you know where to find out how temperatures are converted? a temperature measured on a Fahrenheit thermometer into a Celsius temperature. Don’t worry, this question isn’t a test about your physics knowledge; here is the conversion formula:

Naturally in this formula f is the Fahrenheit temperature and c is the Celsius temperature. While this formula might be good enough for a pre-algebra text book, a mathematician or a programmer would write c(f) on the left side of the equation to remind readers that f is a given value and c is computed from f.

Translating this into BSL is straightforward:

(define (f2c f) (* 5/9 (- f 32)))

Recall that 5/9 is a number, a rational fraction to be precise, and more importantly, that c depends on the given f, which is what the function notation expresses.

> (f2c 32) 0

> (f2c 212) 100

> (f2c -40) -40

(define (convert in out) (write-file out (number->string (f2c (string->number (read-file in))))))

(read-file in) retrieves the content of the file called in as a string;

string->number turns this string into a number;

f2c interprets the number as a Fahrenheit temperature and converts it into a Celsius temperature;

number->string consumes this Celsius temperature and turns it into a string;

and (write-file out ...) places this string into the file named out.

> (write-file "sample.dat" "212") "sample.dat"

> (convert "sample.dat" 'stdout) 100

'stdout

> (convert "sample.dat" "out.dat") "out.dat"

> (read-file "out.dat") "100"

(define (convert in out) (write-file out (number->string (f2c (string->number (read-file in)))))) (define (f2c f) (* 5/9 (- f 32))) (convert "sample.dat" "out.dat")

In addition to running the batch program, it is also instructive to step through the computation. Make sure that the file "sample.dat" exists and contains just a number, then click the STEP button in DrRacket. Doing so opens another window in which you can peruse the computational process that the call to the main function of a batch program triggers. You will see that the process follows the above outline.

Exercise 27. Recall the letter program from Composing Functions. We launched this program once, with the inputs "Matthew", "Fisler", and "Felleisen". Here is how to launch the program and have it write its output to the interactions area:

> (write-file 'stdout (letter "Matthew" "Fisler" "Felleisen"))

Dear Matthew,

We have discovered that all people with the last name

Fisler have won our lottery. So, Matthew,

hurry and pick up your prize.

Sincerely,

Felleisen

'stdout

Of course, programs are useful because you can launch them for many different inputs, and this is true for letter, too. Run letter on three inputs of your choice.

Here is a letter-writing batch program that reads names from three files and writes a letter to one:

(define (main in-fst in-lst in-signature out) (write-file out (letter (read-file in-fst) (read-file in-lst) (read-file in-signature)))) The function consumes four strings: the first three are the names of input files and the last one serves as output file. It uses the first three to read one string each from the three named files, hands these strings to letter, and eventually writes the result of this function call into the file named by out, the fourth argument to main.Create appropriate files, launch main, and check whether it delivers the expected letter.

Note: Once you understand Programming With Lists, you will be able to use other functions from "batch-io", and then you will have no problem writing letters for tens of thousands of lucky lottery winners.

Interactive Programs No matter how you look at it, batch programs are old-fashioned. Even if businesses have used them for decades to automate useful tasks, people prefer interactive programs. Indeed, in this day and age, people mostly interact with desktop applications via a keyboard and a mouse generating input events such as key presses or mouse clicks. Furthermore, interactive programs can also react to computer-generated events, for example, clock ticks or the arrival of a message from some other computer.

Exercise 28. Most people no longer use desktop computers to run applications but cell phones, tablets, and their cars’ information control screens. Soon people will use wearable computers in the form of intelligent glasses, clothes, and sports gear. In the somewhat more distant future, people may come with built-in bio computers that directly interact with body functions. Think of ten different forms of events that software applications on such computers will have to deal with.

This purpose of this section is to introduce the mechanics of writing interactive BSL programs. Because most large example in this book are interactive programs, we introduce the ideas slowly and carefully. You may wish to return to this section when you tackle some of the interactive programming projects; a second or third reading may clarify some of the advance aspects of the mechanics.

By itself, a raw computer is a useless piece of physical equipment. It is called hardware because you can touch it. This equipment becomes useful once you install software, that is, a suite of programs. Usually the first piece of software to be installed on a computer is an operating system. It has the task of managing the computer for you, including connected devices such as the monitor, the keyboard, the mouse, the speakers, and so on. The way it works is that when a user presses a key on the keyboard, the operating system runs a function that processes key strokes. We say that the key stroke is a key event, and the function is an event handler. In the same vein, the operating system runs an event handler for clock ticks, for mouse actions, and so on. Conversely, after an event handler is done with its work, the operating system may have to change the image on the screen, ring a bell, or print a document. To accomplish these tasks, it also runs functions that translate the operating system’s data into sounds, images, and actions on the printer.

Naturally, different programs have different needs. One program may interpret key strokes as signals to control a nuclear reactor; another passes them to a word processor. To make a general-purpose computer work on these radically different tasks, different programs install different event handlers. That is, a rocket launching program uses one kind of function to deal with clock ticks while an oven’s service functions uses a different kind.

Designing an interactive program requires a way to designate some function as the one that takes care of keyboard events, another function for dealing with clock tick, a third one for presenting some data as an image, and so forth. It is the task of an interactive program’s main function to communicate these designations to the operating system, that is, the software platform on which the program is launched.

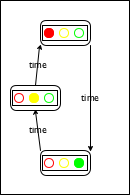

DrRacket is a small operating system and BSL, one of its programming languages, comes with the "universe" teachpack, which provides this communication mechanisms. That is, big-bang is your means to install event handlers and functions that translate data into presentable form. A big-bang expression consists of one required subexpression and one required clause. The subexpression evaluates to the initial state of the program, and the required clause tells DrRacket how to render the current state as a program.

> (number->square 5)

> (number->square 10)

> (number->square 20)

every time the clock ticks, subtract 1 from the current state;

then check whether zero? is true of the new state and if so, stop; and

every time an event handler is finished with its work, use number->square to render the state as an image.

Stop! Explain in your own words how the expression is evaluated.

100, 99, 98, ..., 2, 1, 0

(define (reset s ke) 100)

Stop! Explain what happens when you evaluate this expression, count to 10, and press "a".

What you will see is that the red square shrinks again, one pixel per clock tick. As soon as you press the "a" key on the keyboard though, the red square re-inflates to full size, because reset is called on the current length of the square and "a" and returns 100. This number becomes big-bang’s new state and number->square renders it as a full-sized red square.

The evaluation of this big-bang expression starts with cw0, which is usually an expression. DrRacket, our operating system, installs the value of cw0 as the current state of the world, for short current world. It uses render to translate the current world into an image, which is then displayed in a separate window. Indeed, render is the only means for a big-bang expression to present data to the external world.

Every time the clock ticks, DrRacket applies tock to big-bang’s current world and receives a value in response; big-bang treats this return value as the next current world.

Every time a key is pressed, DrRacket applies ke-h to big-bang’s current world and a string that represents the key; for example, pressing the “a” key is represented with "a" and the left arrow key with "left". When ke-h returns a value, big-bang treats it as the next current world.

Every time a mouse enters the window, leaves it, moves, or is pressed, DrRacket applies me-h to big-bang’s current world, the event’s x and y coordinates, and a string that represents the kind of mouse event that happened; for example, pressing a mouse’s button is represented with "button-down". When me-h returns a value, big-bang treats it as the next current world.

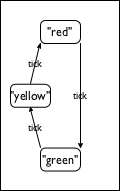

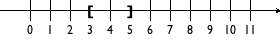

tick #

1

2

3

...

current world

cw0

cw1

cw2

...

its image

(render cw0)

(render cw1)

(render cw2)

...

on clock tick

(tock cw0)

(tock cw1)

(tock cw2)

...

on key stroke

(ke-h cw0 ...)

(ke-h cw1 ...)

(ke-h cw2 ...)

...

on mouse event

(me-h cw0 ...)

(me-h cw1 ...)

(me-h cw2 ...)

...

The table in figure 7 concisely summarizes this process. In the first row, it specifies the current time: the first clock tick, the second, and so forth. The second row associates the current time with a current world. With render, this series of current worlds is mapped to a series of images, which is displayed in the separate window. The last three rows specify the result of applying tock, ke-h, or me-h to the current world and additional data as needed. Only one of these three expressions is evaluated; no matter which one, its result appears in the next column in row 1 as the next current world.

cw1 is the result of (ke-h cw0 "a"), i.e., the fourth cell in the e1 column;

cw2 is the result of (tock cw1), i.e., the third cell in the e2 column;

cw3 is the result of (me-h cw3 90 100 "button-down").

(define cw3 (me-h (tock (ke-h w0 "a")) 90 100 "button-down"))

In short, the sequence of events determines in which order you traverse the above tables of possible worlds to arrive at the one and only one current world for each time slot. Note that DrRacket does not touch the current world; it merely safeguards it and passes it to event handlers and other functions when needed.

(define (main y) (big-bang y [on-tick sub1] [stop-when zero?] [to-draw place-dot-at] [on-key stop])) (define (place-dot-at y) (place-image (circle 3 "solid" "red") 50 y (empty-scene 100 100))) (define (stop y ke) 0)

> (place-dot-at 89)

> (place-dot-at 22)

> (stop 89 "q") 0

> (main 90)

Take a deep breath.

By now, you may feel that these first two chapters are overwhelming. They introduced so many new concepts, including a new language, its vocabulary, its meaning, its idioms, a tool for writing down texts in this vocabulary, running these so-called “programs,” and the inevitable question of how to create them when presented with a problem statement. To overcome this feeling, the next chapter takes a step back and explains how to design programs systematically from scratch, especially interactive programs. So take a breather and continue when ready.

3 How To Design Programs

The first few chapters of this book show that learning to program requires some mastery of many concepts. On the one hand, programming needs some language, a notation for communicating what we wish to compute. The languages for formulating programs are artificial constructions, though acquiring a programming language shares some elements with acquiring a natural language: we need to learn the vocabulary of the programming language, to figure out its grammar, and to understand what its "phrases" mean.

On the other hand, it is critical to learn how to get from a problem statement to a program. We need to determine what is relevant in the problem statement and what can be ignored. We need to tease out what the program consumes, what it produces, and how it relates inputs to outputs. We have to know, or find out, whether the chosen language and its libraries provide certain basic operations for the data that our program is to process. If not, we might have to develop auxiliary functions that implement these operations. Finally, once we have a program, we must check whether it actually performs the intended computation. And this might reveal all kinds of errors, which we need to be able to understand and fix.

All this sounds rather complex and you might wonder why we don’t just muddle our way through, experimenting here and there, leaving well enough alone when the results look decent. This approach to programming, often dubbed “garage programming,” is common and succeeds on many occasions; sometimes it is the launching pad for a start-up company. Nevertheless, the start-up cannot sell the results of the “garage effort” because only the original programmers and their friends can use them.

A good program comes with a short write-up that explains what it does, what inputs it expects, and what it produces. Ideally, it also comes with some assurance that it actually works. In the best circumstances, the program’s connection to the problem statement is evident so that a small change to the problem statement is easy to translate into a small change to the program. Software engineers call this a “programming product.”

The word “other” also includes older versions of the programmer who usually cannot recall all the thinking that the younger version put into the production of the program.

All this extra work is necessary because programmers don’t create programs for themselves. Programmers write programs for other programmers to read, and on occasion, people run these programs to get work done. Most programs are large, complex collections of collaborating functions, and nobody can write all these functions in a day. Programmers join projects, write code, leave projects; others take over their programs and work on them. Another difficulty is that the programmer’s clients tend to change their mind about what problem they really want solved. They usually have it almost right, but more often than not, they get some details wrong. Worse, complex logical constructions such as programs almost always suffer from human errors; in short, programmers make mistakes. Eventually someone discovers these errors and programmers must fix them. They need to re-read the programs from a month ago, a year ago, or twenty years ago and change them.

Exercise 29. Research the “year 2000” problem and what it meant for programmers.

In this book, we present a design recipe that integrates a step-by-step

process with a way of organizing programs around problem data. For the

readers who don’t like to stare at blank screens for a long time, this

design recipe offers a way to make progress in a systematic manner. For

those of you who teach others to design programs, the recipe is a device

for diagnosing a novice’s difficulties. For others, our recipe might be

something that they can apply to other areas, say medicine, journalism, or

engineering. For those who wish to become real programmers, the design

recipe also offers a way to understand and work on existing

programs—

3.1 Designing Functions

Information and Data The purpose of a program is to describe a

computational process of working through information and producing new

information. In this sense, a program is like the instructions a

mathematics teacher gives to grade school students. Unlike a student,

however, a program works with more than numbers; it calculates with

navigation information, looks up a person’s address, turns on switches, or

inspects the state of a video game. All this information comes from a part

of the real world—

Information plays a central role in our description. Think of information as facts about the program’s domain. For a program that deals with a furniture catalog, a “table with five legs” or a “square table of two by two meters” are pieces of information. A game program deals with a different kind of domain, where “five” might refer to the number of pixels per clock tick that some objects travels on its way from one part of the screen to another. Or, a payroll program is likely to deal with “five deductions.”

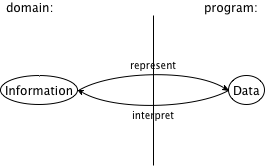

For a program to process information, it must turn it into some form of data, also called values, in the programming language; then it processes the data; and once it is finished, it turns the resulting data into information again. An interactive program may even intermingle these steps, acquiring more information from the world as needed and delivering information in between.

We use BSL and DrRacket so that you do not have to worry about the translation of information into data. In DrRacket’s BSL you can apply a function directly to data and observe what it produces. As a result, we avoid the serious chicken-and-egg problem of writing functions that convert information into data and vice versa. For simple kinds of information, designing such program pieces is trivial; for anything other than simple information, you need to know about parsing, for example, and that immediately requires a lot of expertise in program design.

Software engineers use the slogan model-view-control (MVC) for the way BSL and DrRacket separate data processing from parsing information into data and turning data into information. Indeed, it is now accepted wisdom that well-engineered software systems enforce this separation, even though most introductory books still co-mingle them. Thus, working with BSL and DrRacket allows you to focus on the design of the core of programs and, when you have enough experience with that, you can learn to design the information-data translation parts.

Here we use the "batch-io" and "universe" teachpacks to demonstrate

how complete programs are designed. That is, this book—

Given the central role of information and data, program design must clearly

start with the connection between them. Specifically, we—

42 may refer to the number of pixels from the top margin in the domain of images;

42 may denote the number of pixels per clock tick that a simulation or game object moves;

42 may mean a temperature, on the Fahrenheit, Celsius, or Kelvin scale for the domain of physics;

42 may specify the size of some table if the domain of the program is a furniture catalog; or

42 could just count the number of chars a batch program has read.

Computer scientists use “class” to mean something like a “mathematical set.” They also say that a value is an element of a class.

Since this knowledge is so important for everyone who reads the program, we often write it down in the form of comments, which we call data definitions. The purpose of a data definition is two-fold. On the one hand, it names a class or a collection of data, typically using a meaningful word. On the other hand, it informs readers how to create elements of this class of data and how to decide whether some random piece of data is an element of this collection.

; Temperature is a Number. ; interp. degrees Celsius

If you happen to know that the lowest possible temperatures is approximately -274C, you may wonder whether it is possible to express this knowledge in a data definition. Since data definitions in BSL are really just English descriptions of classes, you may indeed define the class of temperatures in a much more accurate manner than shown here. In this book, we use a stylized form of English for such data definitions, and the next chapter introduces the style for imposing constraints such as “larger than -274.”

At this point, you have encountered the names of some classes of data: Number, String, Image, and Boolean values. With what you know right now, formulating a new data definition means nothing more than introducing a new name for an existing form of data, for example, “temperature” for numbers. Even this limited knowledge, though, suffices to explain the outline of our design process.

- Express how you wish to represent information as data. A one-line comment suffices, for example,

; We use plain numbers to represent temperatures.

Formulate data definitions, like the one for Temperature above for the classes of data you consider critical for the success of your program. Write down a signature, a purpose statement, and a function header.

A function signature (shortened to signature here) is a BSL comment that tells the readers of your design how many inputs your function consumes, from what collection of data they are drawn, and what kind of output data it produces. Here are three examples:- for a function that consumes one string and produces a number:

- for a function that consumes a temperature and that produces a string:

; Temperature -> String

As this signature points out, introducing a data definition as an alias for an existing form of data makes it easy to read the intention behind signatures.Nevertheless, we recommend to stay away from aliasing data definitions for now. A proliferation of such names can cause quite some confusion. It takes practice to balance the need for new names and the readability of programs, and there are more important ideas to understand for now.

- for a function that consumes a number, a string, and an image and that produces an image:

A purpose statement is a BSL comment that summarizes the purpose of the function in a single line. If you are ever in doubt about a purpose statement, write down the shortest possible answer to the questionwhat does the function compute?

Every reader of your program should understand what your functions compute without having to read the function itself.A multi-function program should also come with a purpose statement. Indeed, good programmers write two purpose statements: one for the reader who may have to modify the code and another one for the person who wishes to use the program but not read it.

Finally, a header is a simplistic function definition, also called a stub. Pick one parameter for each input data class in the signature; the body of the function can be any piece of data from the output class. The following three function headers match the above three signatures:(define (f a-string) 0)

(define (g n) "a")

(define (h num str img) (empty-scene 100 100))

Our parameter names reflect what kind of data the parameter represents. Sometimes, you may wish to use names that suggest the purpose of the parameter.When you formulate a purpose statement, it is often useful to employ the parameter names to clarify what is computed. For example,; Number String Image -> Image ; add s to img, y pixels from top, 10 pixels to the left (define (add-image y s img) (empty-scene 100 100)) At this point, you can click the RUN button and experiment with the function. Of course, the result is always the same value, which makes these experiments quite boring.

Illustrate the signature and the purpose statement with some functional examples. To construct a functional example, pick one piece of data from each input class from the signature and determine what you expect back.

Suppose you are designing a function that computes the area of a square. Clearly this function consumes the length of the square’s side, and that is best represented with a (positive) number. The first process step should have produced something like this:

; Number -> Number ; compute the area of a square whose side is len (define (area-of-square len) 0) Add the examples between the purpose statement and the function header:

; Number -> Number ; compute the area of a square whose side is len ; given: 2, expect: 4 ; given: 7, expect: 49 (define (area-of-square len) 0) The next step is to take inventory,We owe the term “inventory” to Dr. Stephen Bloch. to understand what are the givens and what we do need to compute. For the simple functions we are considering right now, we know that they are given data via parameters. While parameters are placeholders for values that we don’t know yet, we do know that it is from this unknown data that the function must compute its result. To remind ourselves of this fact, we replace the function’s body with a template.

For now, the template contains just the parameters, e.g.,; Number -> Number ; compute the area of a square whose side is len ; given: 2, expect: 4 ; given: 7, expect: 49 (define (area-of-square len) (... len ...)) The dots remind you that this isn’t a complete function, but a template, a suggestion for an organization.The templates of this section look boring. Later, when we introduce complex forms of data, templates become interesting, too.

It is now time to code. In general, to code means to program, though often in the narrowest possible way, namely, to write executable expressions and function definitions.

To us, coding means to replace the body of the function with an expression that attempts to compute from the pieces in the template what the purpose statement promises. Here is the complete definition for area-of-square:; Number -> Number ; compute the area of a square whose side is len ; given: 2, expect: 4 ; given: 7, expect: 49 (define (area-of-square len) (sqr len)) To complete the add-image function takes a bit more work than that:; Number String Image -> Image ; add s to img, y pixels from top, 10 pixels to the left ; given: ; 5 for y, ; "hello" for s, and ; (empty-scene 100 100) for img ; expected: ; (place-image (text "hello" 10 "red") 10 5 (empty-scene 100 100)) (define (add-image y s img) (place-image (text s 10 "red") 10 y img)) In particular, the function needs to turn the given string s into an image, which is then placed into the given scene.- The last step of a proper design is to test the function on the examples that you worked out before. For now, click the RUN button and enter function applications that match the examples in the interactions area:

> (area-of-square 2) 4

> (area-of-square 7) 49

The results must match the output that you expect; you must inspect each result and make sure it is equal to what is written down in the example portion of the design. If the result doesn’t match the expected output, consider the following three possibilities:You miscalculated and determined the wrong expected output for some of the examples.

Alternatively, the function definition computes the wrong result. When this is the case, you have a logical error in your program, also known as a bug.

Both the examples and the function definition are wrong.

When you do encounter a mismatch between expected results and actual values, we recommend that you first re-assure yourself that the expected results are correct. If so, assume that the mistake is in the function definition. Otherwise, fix the example and then run the tests again. If you are still encountering problems, you may have encountered the third, somewhat rare situation.

3.2 Finger Exercises

The first few of the following exercises are almost copies of previous ones. The difference is that this time they used the word “design” not “define,” meaning you should use the design recipe to create these functions and your solutions should include all relevant pieces. (Skip the template; it is useless here.) Finally, as the title of the section suggests these exercises are practice exercises to help you internalize the process. Until the steps become second nature, never skip one; that leads to easily avoided errors and unproductive searches for the causes of those flaws. There is plenty of room left in programming for complicated errors; we have no need to waste our time on silly ones.

Exercise 30. Design the function string-first, which extracts the first character from a non-empty string. Don’t worry about empty strings.

Exercise 31. Design the function string-last, which extracts the last character from a non-empty string.

Exercise 32. Design the function image-area, which counts the number of pixels in a given image.

Exercise 33. Design the function string-rest, which produces a string like the given one with the first character removed.

Exercise 34. Design the function string-remove-last, which produces a string like the given one with the last character removed.

3.3 Domain Knowledge

Knowledge from external domains such as mathematics, music, biology, civil engineering, art, etc. Because programmers cannot know all of the application domains of computing, they must be prepared to understand the language of a variety of application areas so that they can discuss problems with domain experts. This language is often that of mathematics, but in some cases, the programmers must learn a language as they work through problems with domain experts.

And knowledge about the library functions in the chosen programming language. When your task is to translate a mathematical formula involving the tangent function, you need to know or guess that your chosen language comes with a function such as BSL’s tan. When, however, you need to use BSL to design image-producing functions, you will benefit from understanding the possibilities of the "2htdp/image" teachpack.

You can recognize problems that demand domain knowledge from the data definitions that you work out. As long as the data definitions use classes that exist in the chosen programming language, the definition of the function body (and program) mostly relies on expertise in the domain. Later, when we introduce complex forms of data, the design of functions demands computer science knowledge.

3.4 From Functions to Programs

Not all programs consist of a single function definition. Some require several functions, many also use constant definitions. No matter what, it is always important to design each function of a program systematically, though both global constants and the presence of auxiliary functions change the design process a bit.

When you have defined global constants, your functions may use those global constants to compute results. To remind yourself of their existence, you may wish to add these constants to your templates; after all, they belong to the inventory of things that may contribute to the function definition.

Multi-function programs come about because interactive programs automatically need event handling functions, state rendering functions, and possibly more. Even batch programs may require several different functions because they perform several separate tasks. Sometimes the problem statement itself suggests these tasks; other times you will discover the need for auxiliary functions as you are in the middle of designing some function.

For these reasons, we recommend keeping around a list of needed functions or a wish list.We owe the term “wish list” to Dr. John Stone. Each entry on a wish list should consist of three things: a meaningful name for the function, a signature, and a purpose statement. For the design of a batch program, put the main function on the wish list and start designing it. For the design of an interactive program, you can put the event handlers, the stop-when function, and the scene-rendering function on the list. As long as the list isn’t empty, pick a wish and design the function. If you discover during the design that you need another function, put it on the list. When the list is empty, you are done.

3.5 On Testing

Testing quickly becomes a labor-intensive chore. While it is easy to run

small programs in the interactions area, doing so requires a lot of

mechanical labor and intricate inspections. As programmers grow their

systems, they wish to conduct many tests. Soon this labor becomes

overwhelming, and programmers start to neglect it. At the same

time, testing is the first tool for discovering and preventing basic

flaws. Sloppy testing quickly leads to buggy functions—

; Number -> Number ; convert Fahrenheit temperatures to Celsius temperatures ; given 32, expected 0 ; given 212, expected 100 ; given -40, expected -40 (define (f2c f) (* 5/9 (- f 32)))

(check-expect (f2c -40) -40) (check-expect (f2c 32) 0) (check-expect (f2c 212) 100)

(check-expect (f2c -40) 40)

; Number -> Number ; convert Fahrenheit temperatures to Celsius temperatures (check-expect (f2c -40) -40) (check-expect (f2c 32) 0) (check-expect (f2c 212) 100) (define (f2c f) (* 5/9 (- f 32)))

You can place check-expect specifications above or below the

function definitions that they test. When you click RUN, DrRacket

collects all check-expect specifications and evaluates them

after all function definitions have been added to the

“vocabulary” of operations. The above figure shows how to exploit this

freedom to combine the example and test step. Instead of writing down the

examples as comments, you can translate them directly into tests. When

you’re all done with the design of the function, clicking RUN

performs the test. And if you ever change the function for some

reason—

(check-expect (render 50) )

(check-expect (render 200) )

(check-expect (render 50) (place-image CAR 50 Y-CAR BACKGROUND)) (check-expect (render 200) (place-image CAR 200 Y-CAR BACKGROUND))

Because it is so useful to have DrRacket conduct the tests and not to check everything yourself manually, we immediately switch to this style of testing for the rest of the book. This form of testing is dubbed unit testing, and BSL’s unit testing framework is especially tuned for novice programmers. One day you will switch to some other programming language; one of your first tasks will be to figure out its unit testing framework.

3.6 Designing World Programs

While the previous chapter introduces the "universe" teachpack in an ad hoc way, this section demonstrates how the design recipe helps you create world programs systematically. It starts with a brief summary of "universe" based on data definitions and function signatures. The second part spells out a design recipe for world programs, and the last one starts a series of exercises that runs through several of the next few chapters.

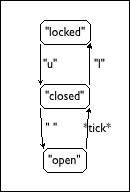

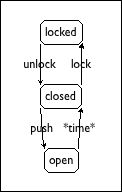

Figure 10 presents "universe" in a schematic and simplified way. The teachpack expects that a programmer develops a data definition that represents the state of the world and a function render that knows how to create an image for every possible state of the world. Depending on the needs of the program, the programmer must then design functions that respond to clock ticks, key strokes, and mouse events. Finally, an interactive program may need to stop when its current world belongs to a sub-class of states; end? recognizes these final states.

; WorldState : a data definition of your choice ; a collection of data that represents the state of the world ; render : ; WorldState -> Image ; big-bang evaluates (render cw) to obtain image of ; current world cw ; clock-tick-handler : ; WorldState -> WorldState ; for each tick of the clock, big-bang evaluates ; (clock-tick-handler cw) for current world cw to obtain ; new world ; key-stroke-handler : ; WorldState String -> WorldState ; for each key stroke, big-bang evaluates ; (key-stroke-handler cw ke) for current world cw and ; key stroke ke to obtain new world ; mouse-event-handler : ; WorldState Number Number String -> WorldState ; for each key stroke, big-bang evaluates ; (mouse-event-handler cw x y me) for current world cw, ; coordinates x and y, and mouse event me to ; obtain new world ; end? : ; WorldState -> Boolean ; after an event is processed, big-bang evaluates (end? cw) ; for current world cw to determine whether the program stops

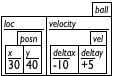

Sample Problem: Design a program that moves a car across the world canvas, from left to right, at the rate of three pixels per clock tick.

- For all those properties of the world that remain the same over time and are needed to render it as an Image, introduce constants. In BSL, we specify such constants via definitions. For the purpose of world programs, we distinguish between two kinds of constants:

“Physical” constants describe general attributes of objects in the world, such as the speed or velocity of an object, its color, its height, its width, its radius, and so forth. Of course these constants don’t really refer to physical facts, but many are analogous to physical aspects of the real world.

In the context of our sample problem, the radius of the car’s wheels and the distance between the wheels are such “physical” constants:Note how the second constant is computed from the first.Graphical constants are images of objects in the world. The program composes them into images that represent the complete state of the world.

We suggest you experiment in DrRacket’s interaction area to develop graphical constants.

Here are graphical constants for wheel images of our sample car:(define WHEEL (circle WHEEL-RADIUS "solid" "black")) (define SPACE (rectangle ... WHEEL-RADIUS ... "white")) (define BOTH-WHEELS (beside WHEEL SPACE WHEEL)) Graphical constants are usually computed, and the computations tend to involve the physical constants and other graphical images.

Those properties that change over time—

in reaction to clock ticks, key strokes, or mouse actions— give rise to the current state of the world. Your task is to develop a data representation for all possible states of the world. The development results in a data definition, which comes with a comment that tells readers how to represent world information as data and how to interpret data as information about the world. Choose simple forms of data to represent the state of the world.

For the running example, it is the car’s distance to the left margin that changes over time. While the distance to the right margin changes, too, it is obvious that we need only one or the other to create an image. A distance is measured in numbers, so the following is an adequate data definition:

An alternative is to count the number of clock ticks that have passed and to use this number as the state of the world. We leave this design variant as an exercise.Once you have a data representation for the state of the world, you need to design a number of functions so that you can form a valid big-bang expression.

To start with, you need a function that maps any given state into an image so that big-bang can render the sequence of states as images:; render

Next you need to decide which kind of events should change which aspects of the world state. Depending on your decisions, you need to design some or all of the following three functions:; clock-tick-handler ; key-stroke-handler ; mouse-event-handler Finally, if the problem statement suggests that the program should stop if the world has certain properties, you must design; end?

For the generic signatures and purpose statements of these functions, see figure 10. You should reformulate these generic purpose statements so that you have a better idea of what your functions must compute.In short, the desire to design an interactive program automatically creates several initial entries for your wish list. Work them off one by one and you get a complete world program.

Let us work through this step for the sample program. While big-bang dictates that we must design a rendering function, we still need to figure out whether we want any event handling functions. Since the car is supposed to move from left to right, we definitely need a function that deals with clock ticks. Thus, we get this wish list:; WorldState -> Image ; place the image of the car x pixels from the left margin of ; the BACKGROUND image (define (render x) BACKGROUND) ; WorldState -> WorldState ; add 3 to x to move the car right (define (tock x) x) Note how we tailored the purpose statements to the problem at hand, with an understanding of how big-bang will use these functions.Finally, you need a main function. Unlike all other functions, a main function for world programs doesn’t demand design. It doesn’t even require testing because its sole reason for existing is that you can launch your world program conveniently from DrRacket’s interaction area.

The one decision you must make concerns main’s arguments. For our sample problem we opt to apply main to the initial state of the world:; main : WorldState -> WorldState ; launch the program from some initial state (define (main ws) (big-bang ws [on-tick tock] [to-draw render])) Hence, you can launch this interactive program with> (main 13)

Let us now work through the rest of the program design process, using the design recipe for functions and other design concepts spelled out so far.

Exercise 35. Good programmersGood programmers establish a single point of control for all aspects of their programs, not just the graphical constants. Several chapters deal with this issue. ensure that an image such as CAR can be enlarged or reduced via a single change to a constant definition. We started the development of our car image with a single plain definition:(define WHEEL-RADIUS 5)

The definition of WHEEL-DISTANCE is based on the wheel’s radius. Hence, changing WHEEL-RADIUS from 5 to 10 doubles of the car image. This kind of program organization is dubbed single point of control, and good design employs single point of control as much as possible.Develop your favorite image of a car so that WHEEL-RADIUS remains the single point of control. Remember to experiment and make sure you can re-size the image easily.

; WorldState -> WorldState ; the clock ticked; move the car by three pixels (define (tock ws) ws)

; WorldState -> WorldState ; the clock ticked; move the car by three pixels ; example: ; given: 20, expected 23 ; given: 78, expected 81 (define (tock ws) (+ ws 3))

> (tock 20) 23

> (tock 78) 81

; WorldState -> Image ; place the car into a scene, according to the given world state (define (render ws) BACKGROUND)

ws = | 50 |

|

ws = | 100 |

|

ws = | 150 |

|

ws = | 200 |

|

ws = | 50 |

|

ws = | 100 |

|

ws = | 150 |

|

ws = | 200 |

|

; WorldState -> Image ; place the car into a scene, according to the given world state (define (render ws) (place-image CAR ws Y-CAR BACKGROUND))

Exercise 37. Finish the sample problem and get the program to run. That is, assuming that you have solved exercise 35, define the constants BACKGROUND and Y-CAR. Then assemble all the function definitions, including their tests. When your program runs to your satisfaction, add a tree to scenery. We used

(define tree (underlay/xy (circle 10 'solid 'green) 9 15 (rectangle 2 20 'solid 'brown))) to create a tree-like shape. Also add a clause to the big-bang expression that stops the animation when the car has disappeared on the right side of the canvas.

After settling on a first data representation for world states, a careful

programmer may have to revisit this fundamental design decision during the

rest of the design process. For example, the data definition for the sample

problem represents the car as a point. But (the image of) the car isn’t

just a mathematical point without width and height. Hence, the

interpretation statement—

Exercise 38. Modify the interpretation of the sample data definition so that a state denotes the x coordinate of the right-most edge of the car.

Like the original data definition, this one also equates the states of the world with the class of numbers. Its interpretation, however, explains that the number means something entirely different.Design functions tock and render and develop a big-bang expression so that you get once again an animation of a car traveling from left to right across the world’s canvas.

How do you think this program relates to the animate function from Prologue: How to Program?

Use the data definition to design a program that moves the car according to a sine wave. Don’t try to drive like that.

Sample Problem: Design a program that moves a car across the world canvas, from left to right, at the rate of three pixels per clock tick. If the mouse is clicked anywhere on the canvas, the car is placed at that point.

There are no new properties, meaning we do not need new physical or graphical constants.

Since the program is still concerned with only one property that changes over time—

the location of the car— the existing data representation suffices. - The problem statement now explicitly calls for a mouse event handler, without giving up on the clock-based movement of the car. Hence, we merely add an appropriate wish to our list:

; WorldState Number Number String -> WorldState ; place the car at the position (x,y) ; if the mouse event is "button-down" (define (hyper x-position-of-car x-mouse y-mouse me) x-position-of-car) - Lastly, we need to modify our main function to take care of mouse events. All this requires is the addition of an on-mouse clause that defers to the new entry on our wish list:After all, the modified problem statement calls for dealing with mouse clicks and everything else remains the same.

; WorldState Number Number String -> WorldState ; place the car at the mouse position (x,y) ; if the mouse event is "button-down" ; given: 21 10 20 "enter" ; wanted: 21 ; given: 42 10 20 "button-down" ; wanted: 10 ; given: 42 10 20 "move" ; wanted: 42 (define (hyper x-position-of-car x-mouse y-mouse me) x-position-of-car)

Exercise 40. Formulate the examples as BSL tests. Click RUN and watch them fail.

; WorldState Number Number String -> WorldState ; place the car at the mouse position (x,y) ; if the mouse event is "button-down" (define (hyper x-position-of-car x-mouse y-mouse me) (cond [(string=? "button-down" me) x-mouse] [else x-position-of-car]))

(main 1)

You may wonder why this program modification is so straightforward. There

are really two reasons. First, this book and its software strictly separate

the data that a program tracks—

3.7 A Note on Mice and Characters